Simplifying Battery-Less Motor Monitoring Design

Contributed By Electronic Products

2016-05-24

Early detection of failure in motors is essential for minimizing downtime and ensuring safe operation of motor-driven equipment and facilities. Using a thermoelectric generator (TEG), specialized power management IC, wireless MCU, and only a few additional components, engineers can build a wireless sensor system capable of sustained, battery-less operation by extracting energy from the heat of the motor itself.

Significant variations in a motor's operating characteristics can point to imminent or potential failures of the motor. In particular, temperature measurement provides a particularly effective motor-performance metric because many electrical and mechanical problems are directly responsible for increased motor temperatures. For example, high temperature is typically the first indication of bearing trouble. In fact, temperature increase can result from a number of conditions such as high ambient temperature, voltage imbalance, excessive load, contamination, or blocked air intakes — any of which can erode motor performance and shorten its lifespan. Indeed, experience shows that motor life is reduced by 50 percent for each 10°C that its operating temperature exceeds its rated temperature.

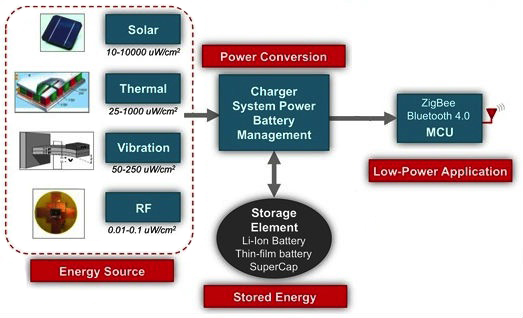

Using a pair of readily available ICs, designers can build a sophisticated wireless-sensor system able to perform a broad range of measurements while drawing power from the heat of the motor itself. At the heart of this design, a specialized energy-harvesting power management IC (PMIC) and wireless MCU provide the essential capabilities needed to extract thermal power and perform sensor measurements (Figure 1). While the PMIC optimizes energy conversion from the TEG and manages an optional storage device, the MCU uses its integrated analog peripherals to collect sensor data and its integrated RF transceiver for wireless communications with a host controller or other devices.

Figure 1: Among ambient-energy sources, thermal energy can deliver significant power particularly in motor monitoring applications; the combination of an energy-harvesting IC and wireless MCU largely completes the design of a wireless sensor system powered by this thermal source and using the MCU's integrated analog peripherals for sensor-data acquisition. (Courtesy of Texas Instruments)

Power requirements

Energy-harvesting methods allow designers to create systems able to operate for years without a need for battery replacement or even without a battery at all. A foremost concern for energy-harvesting applications revolves around the ability of the energy source not only to meet average power requirements but also to handle periodic peak power loads. For wireless applications, the very nature of wireless communications emphasizes these concerns.

A typical wireless transaction comprises both receive and transmit phases when the system first listens for other devices and then transmits its data. For a sensor system, these communications transactions might last only a few milliseconds but occur many seconds (or minutes) apart. As a result, the system typically spends the majority of its time in a low-power idle or sleep state. Consequently, the power-consumption profile of a wireless sensor system is generally characterized by extended quiescent periods interrupted periodically by bursts of activity as the system wakes up from its sleep state, performs its radio transactions, and performs associated post-processing routines before returning its low-power sleep state (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Radio reception and transmission represent peak current demands in most small wireless systems using popular communications protocols such as Bluetooth Low Energy, shown here. (Courtesy of Texas Instruments)

For the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) communications event shown in Figure 2, Texas Instruments engineers found[1] that a CC2541 transceiver IC exhibits peak current levels of 17.5 mA for both reception and transmission. In this case, the engineers measured an average current consumption of 8.3 mA for the complete communications event, which ran about 3 msec in duration. In fact, current requirements are even lower in designs using more recent transceivers such as the TI CC2650.

Built to support a wide variety of wireless protocols, the CC2650 includes an on-chip 2.4 GHz RF transceiver able to support BLE or IEEE 802.15.4 wireless communications. Along with its ARM® Cortex®-M3 host processor, the CC2650 integrates an ultra-low-power ARM Cortex-M0 core dedicated to execution of wireless stacks including Bluetooth Smart®, ZigBee®, and 6LoWPAN. The result is a device able to deliver significant processing and communications capabilities while maintaining very-low-power consumption levels required for energy-harvesting designs.

In contrast to the earlier CC2541, the CC2650 consumes only 5.9 mA in active reception mode and 6.1 mA in active transmission (0 dBm). Furthermore, power consumption in active state is only about 2.8 mA for the CC2650 compared to about 8.3 mA for the CC2541. Thus, current consumption in a design with a recent device such as the CC2650 would be about 6.1 mA peak current and an appreciably lower average current — about a third of that required with the earlier CC2541.

At the same time, the CC2650 features a low-power idle mode that consumes only 500 μA while maintaining power to system supplies and RAM. In fact, the CC2650 features a low-power standby state that consumes only 1 μA with running real-time clock and retaining RAM and CPU state. In the 500 μA idle mode, the device transitions to active mode in only 14 μs, but it requires 151 μs to transition to active mode from the 1 μA standby mode. Although many sensor applications could confidently trade longer wake-up time for lower power consumption, designers would need to carefully assess the trade-off between sleep power requirements and response time.

Beyond these fundamental performance requirements, sensor-data acquisition and signal processing would of course add additional power requirements. Consequently, a particular wireless-sensor application would levy its own unique requirements for factors such as processing load and sleep duration. Nevertheless, this quick analysis suggests an integrated wireless MCU such as the CC2650 or even CC2541 would present power requirements well within the capabilities of energy-harvesting designs — particularly in an application designed to use energy harvested from industrial motors.

Power availability

Industrial motors are specified to allow relatively high increases in operating temperature. Motors rated at National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) class A have an allowable temperature rise of 60°C and NEMA class F motors can increase by 125°C while operating at rated power (that is, service-factor 1.0). With the availability of this abundant thermal energy, energy harvesting using a TEG offers an ideal solution for power generation.

TEGs produce power proportional to the temperature differential between their two faces. Consequently, designers would need to take steps to ensure that the temperature of the "cold" side of TEG remains significantly lower than the motor (hot) side of the TEG. For this application, use of a conventional finned heatsink for convection cooling would in most cases ensure a reasonable temperature differential across the TEG.

In environments with high ambient temperatures, simple convection cooling might result in only a minimal temperature differential — and simultaneously reduced power output. To ensure maximum power output even at low-energy levels, designers need to maintain the TEG at the maximum power point on the TEG power curve. Furthermore, use of a suitable energy storage device might be required to ensure a stable source of power able to meet peak demands during wireless communications transactions despite low levels of sustained energy conversion.

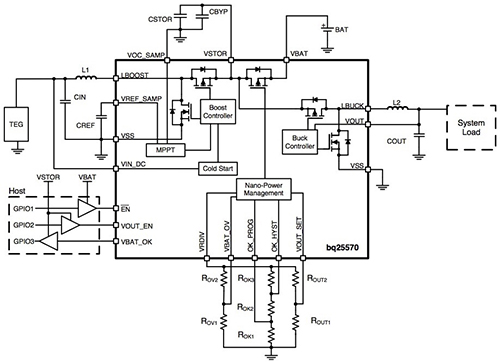

Specialized PMICs such as the TI BQ25570 address these multiple requirements: Along with maximizing power output from the TEG, the BQ25570 can manage the charge and discharge cycles of an energy-storage device — as well as deliver a regulated supply to the wireless MCU. Designed specifically for energy harvesting, the BQ25570 is able to scavenge power from even microwatt energy sources. Its integrated charge management features lets it use even limited harvested power to safely charge rechargeable batteries and supercapacitors while protecting the energy-storage device from overvoltage and undervoltage levels. Finally, an integrated voltage converter provides regulated power output for MCUs and other devices with tight supply requirements. With its extensive set of integrated capabilities, the BQ25570 requires only a few additional components to provide a sophisticated thermal-powered supply (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Highly integrated power management ICs such as the BQ25570 require only a few additional components to convert thermal energy to a regulated output level while also managing an external energy-storage device. (Courtesy of Texas Instruments)

A final design choice for a simplified battery-less wireless sensor system lies in the selection of a suitable energy-storage device. As noted earlier, some motor-monitoring scenarios may generate sufficient energy on a sustained basis to meet peak power requirements. For other applications — and even as power backup for energy-rich environments — supercapacitors offer a particularly attractive solution for wireless sensor systems intended for extended operation.

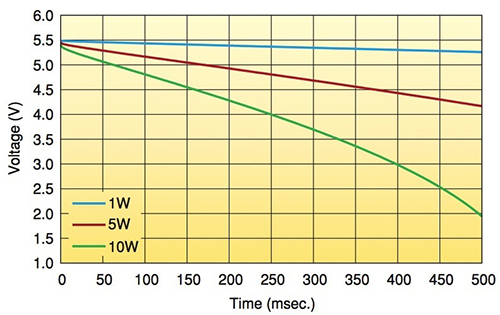

Supercapacitors can maintain capacity through a significantly greater number of charge/discharge cycles than rechargeable batteries of comparable capacity — in many cases, an order of magnitude greater. Furthermore, supercapacitors exhibit very low leakage current: for example, the Murata DMF3Z5R5H474M3DTA0 470 mF supercapacitor leakage current is less than 5 μA over a 96-hour period. As a result, these devices are well-suited to energy-constrained applications such as energy harvesting. At the same time, these devices offer very flexible discharge rates — for example, the DMF3Z5R5H474M3DTA0 offers discharge rates from 400 μAh to 1.5 As. Furthermore, the high-storage capacity of these devices allows them to sustain output voltage for periods well beyond the duration of typical wireless transaction events even at very-high-power levels (Figure 4).

Figure 4: At the low-power levels required by wireless transceivers, supercapacitors can sustain voltage-output levels for periods well beyond the duration of typical wireless transactions. (Courtesy of Murata)

Conclusion

Powered by thermal energy extracted from motor heating, wireless monitoring systems can provide critical information needed to predict motor failure, prevent downtime, and ensure safety. Engineers can build an effective wireless monitoring system that requires only a few additional components beyond a TEG and a pair of highly integrated devices — a specialized PMIC and a wireless MCU. While the PMIC maximizes TEG output and delivers a regulated supply, the MCU collects sensor data and passes it to a host. Using these sophisticated devices, engineers can create motor-monitoring systems capable of sustained battery-less operation.

For more information about the parts discussed in this article, use the links provided to access product pages on the Digi-Key website.

References:

- TI Application Note "Measuring Bluetooth Low Energy Power Consumption (Rev. A)"

Disclaimer: The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the various authors and/or forum participants on this website do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints of DigiKey or official policies of DigiKey.